The system arrived in four metal export containers. It wasn’t necessary to remove anything because the equipment inside was preconfigured. All workers had to do was bolt the containers together.

For something so simple and ready-to-go, Cable Box—a wire chopper manufactured by MTB—has opened new markets for Potomac Metals Inc., a private scrap metal recycling company headquartered in Sterling, Virginia.

Potomac Metals bought its Cable Box toward the end of 2017 through Buffalo, New York-based Wendt Corp., a supplier and integrator of scrap metal processing equipment. The system, up and running by February 2018, has allowed Potomac to make clean chops of No. 1 insulated copper wire (ICW) and insulated aluminum wire and to separate the wire from its plastic covering. The company had never chopped wire before adding the Cable Box.

According to Wendt, the MTB Cable Box can manage other hard-to-process wire and materials, including ICW from auto shredder residue (ASR); aluminum conductor steel-reinforced (ACSR) cable, BX (flexible metal conduit), underground residential distribution (URD) cables, Category 5 computer network cables and aluminum and copper radiators.

Ease of assembly was one reason Potomac chose the Cable Box over other wire choppers, says Jeremy Wong, vice president at Potomac Metals.

“Other systems come in pieces and you have to assemble and align everything,” Wong says. “It can take months. Cable Box is more modular. You can set it up and power it up in a couple of days.”

Price was another factor. Wong says Potomac looked at larger, heavier systems that seemed to handle higher volumes of material, but they were more expensive. So far, Cable Box has handled the company’s maximum input.

Mark Zwilsky, chief executive officer of Potomac Metals, says his firm purchased a special electric crane that can reach 9 feet high to feed material into the Cable Box. With the crane and other accessories, the total cost to buy and install Cable Box—which Potomac runs nine to 10 hours a day, six days per week—was about $2 million.

Thanks to the Cable Box, Potomac no longer sells small-gauge copper and aluminum wire to processing firms, which charge a processing fee. Instead, the firm sells stripped and chopped wire directly to customers, eliminating the third-party processing fee from its budget.

Also, Potomac can now buy and sell more wire, Wong says. Scrap wire is always in demand as new buildings replace older buildings.

Zwilsky says wire had previously represented about one-third of Potomac Metal’s total business. With the addition of the Cable Box, the company’s wire-processing volume has risen by 25 percent to 30 percent, and the wire side of the company’s business has increased by 15 percent to 20 percent.

“We took a chance on Cable Box, and looking back now, it was a really good decision strategically and financially,” Zwilsky says.

A growing concern

Judging from its growth, Potomac Metals must have made several good decisions over the years. Mark Zwilsky founded the company in the mid-1990s with his father, Klaus Zwilsky, and another partner who has since moved on. Mark’s son, Eric Zwilsky, later joined the firm and today is a vice president.

Originally, Potomac maintained a single, 5,000-square-foot building for its office and warehouse and a small box truck. Today, it has a 70,000-square-foot warehouse and eight satellite yards in Virginia, West Virginia and Maryland. The company owns 30 trucks and employs more than 150 workers.

Potomac also spun off a sister company, eCycle, about 12 years ago. It destroys data on and recycles electronic devices.

Potomac Metals buys scrap metal—including aluminum, brass, steel, stainless steel, copper and lead—from industrial, commercial and residential sellers and from federal, state and local governments. It processes and sells the metal to mills, refineries and end users throughout the United States and in other countries, including Malaysia, Hong Kong and Germany.

Suppliers selling scrap metal can drop it off at any Potomac location. The company also can send trucks to industrial and commercial sellers throughout the mid-Atlantic region and pick up material, supplying those firms with Gaylord boxes, rolling carts and drums for metal storage.

Potomac feeds its nonferrous scrap into a two-ram baler from Harris, Cordele, Georgia. It uses wheel loaders, excavators and material handlers to move materials around and alligator shears to cut metal. Mark Zwilsky says because of increasing business, Potomac plans to build another 40,000-square-foot warehouse, which will hold another baler, over the next couple of months.

"I wondered if the motors and granulators would handle the volume we had planned.” – Mark Zwilsky, Potomac Metals

Potomac also has hand-fed strippers, with rollers and blades, that separate metal wire from plastic. It was the company’s only way to process wire before adding the Cable Box.

“It’s a tedious process, requiring more manual labor,” Wong explains. “And we couldn’t do smaller-gauge wire with the stripper.”

Therefore, Potomac sold smaller-gauge wire to processing firms that Mark Zwilsky says charged between 6 cents to 8 cents per pound for the service.

“There are only a select few wire choppers around,” Eric Zwilsky says. “Wire processing is very competitive and secretive. The companies that do it have been around for 50 years and have a competitive edge. Nobody goes out to get training on how to be a wire chopper.”

Nevertheless, within the last few years, Potomac figured it was buying enough small-gauge wire that it was time to process its own.

The volume test

Mark Zwilsky says Potomac first heard about Cable Box from an MTB salesperson. Subsequently, he watched the system in action, along with other equipment, during the June 2017 Demo Days, an event Wendt organized in Buffalo.

Potomac and two other companies that attended Demo Days ended up buying the Cable Box, which Wendt’s website describes as a “turnkey cable recycling line that can handle up to 3 tons of cable an hour.”

_fmt.png)

“Initially, I wasn’t real enthusiastic about buying this machinery,” Mark Zwilsky says, referring to the Cable Box. “I wanted to go with another company that had a different process.

“I thought Cable Box was unproven because we were among the first companies to get one, and I thought it wasn’t big enough,” he explains. “I wondered if the motors and granulators would handle the volume we had planned.”

But the Cable Box has performed well for Potomac Metals. Usually the system processes between 2,000 to 6,000 pounds of metal an hour; but, on busy days, it can handle between 10,000 to 12,000 pounds per hour, which is the most Potomac processes at any given time.

In comparison, Potomac could only process 5,000 pounds per day using its hand-fed wire strippers, Mark Zwilsky says. As a result, Potomac has discarded most of those devices, he notes.

“Whichever ones are left, we seldom use,” Mark Zwilsky adds. “The stuff we did with hand-fed equipment we can handle with Cable Box.”

Wong says the equipment inside the four containers includes a preshredder that downsizes material to pieces about 12 millimeters long. Then conveyor belts move the material to granulators and separation tables that grind the metal further—into pieces as short as 3 millimeters—and separate it from plastic insulation.

Wong says the Cable Box also can separate aluminum from copper if the disparity in density is significant enough.

Costs vs. benefits

From an operating cost perspective, the MTB Cable Box draws a significant amount of electricity, Mark Zwilsky says. Potomac Metals paid about $100,000 to add 800 amps of electrical capacity so it could run the system. The company’s electric bills have increased by more than $6,000 per month since it began operating the Cable Box.

In terms of maintenance, Mark Zwilsky says MTB suggests changing the Cable Box’s blades every 40 hours of operation, but more frequent blade swapping might become necessary, depending on the materials being processed. He says Potomac changes its blades every 45 to 55 hours of operation.

Additionally, Potomac hired five additional workers to operate the Cable Box. Typically, one worker feeds material into the system, while two workers monitor the line. However, in a pinch, two workers can operate the system, Mark Zwilsky says.

He adds that Potomac Metals has discussed processing other types of material with the Cable Box but has not decided to do so as of early summer.

“The output we have now has been very positive,” he says of Potomac’s experience with the Cable Box. “When you start to chop other stuff, my opinion is the machine starts to bog down. We have tried other materials with it already, and that’s what happens.”

Despite the operating costs and potential limitations, Mark Zwilsky says the Cable Box’s benefits—eliminating the wire-processing fee and enabling Potomac to buy and sell more wire—easily outweigh the costs.

“A year and a half after we bought the machine, we believe we made the right decision,” Mark Zwilsky says. “I wasn’t sure if it could do what we needed it to do, but it has worked out well for us.”

Explore the August 2019 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find you next story to read.

Latest from Recycling Today

- Cyclic Materials expands leadership team

- Paper cup acceptance at US mills reaches new milestone

- EPA announces $3B to replace lead service lines

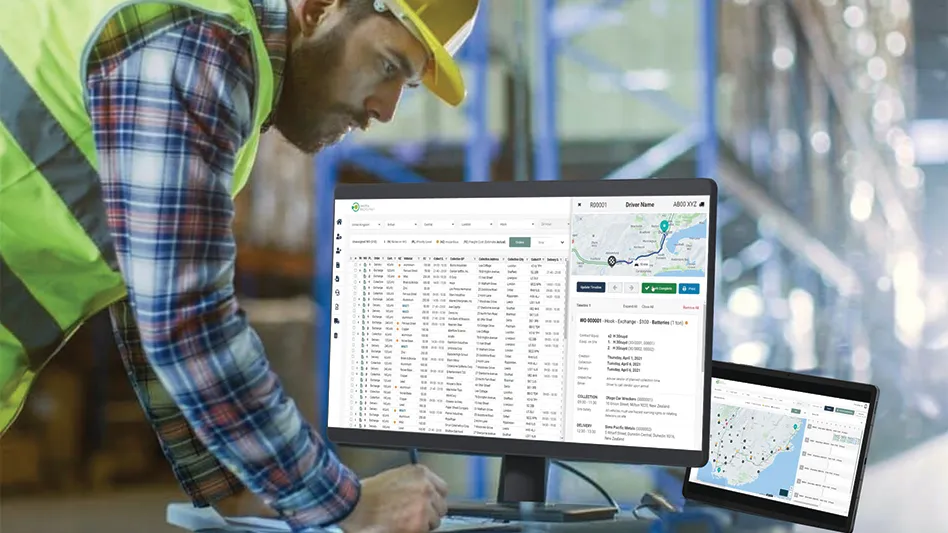

- AMCS showcasing Performance Sustainability Suite at WasteExpo

- New Way and Hyzon unveil first hydrogen fuel cell refuse truck

- Origin Materials introduces tethered PET beverage cap

- Rubicon selling fleet technology business, issuing preferred equity to Rodina Capital

- Machinex to feature virtual tour of Rumpke MRF at WasteExpo