frog | stock.adobe.com

Rare earth elements (REEs), essential components in the magnets used in e-motors and wind turbines, are key to enabling the energy transition. However, REE mining and refining are highly concentrated in China, which recently enacted export restrictions on specific medium and heavy REEs. Many countries also have identified REEs as being critical to their resiliency, creating opportunities for circular supply chains if recovery challenges can be overcome, according to a new report from McKinsey & Co. titled “Powering the energy transition’s motor: Circular rare earth elements.”

The 11-page report, written by Michel van Hoey, Peter Spiller and Sebastian Göke, with H. Jens Rempe, Patricia Bingoto and Vladislav Vasilenko, represents views from the company’s Energy & Materials Practice.

It is the final report in a six-part McKinsey “Materials Circularity” series, with previous reports having examined the recycling landscape for basic materials overall, aluminum, copper, glass and plastics.

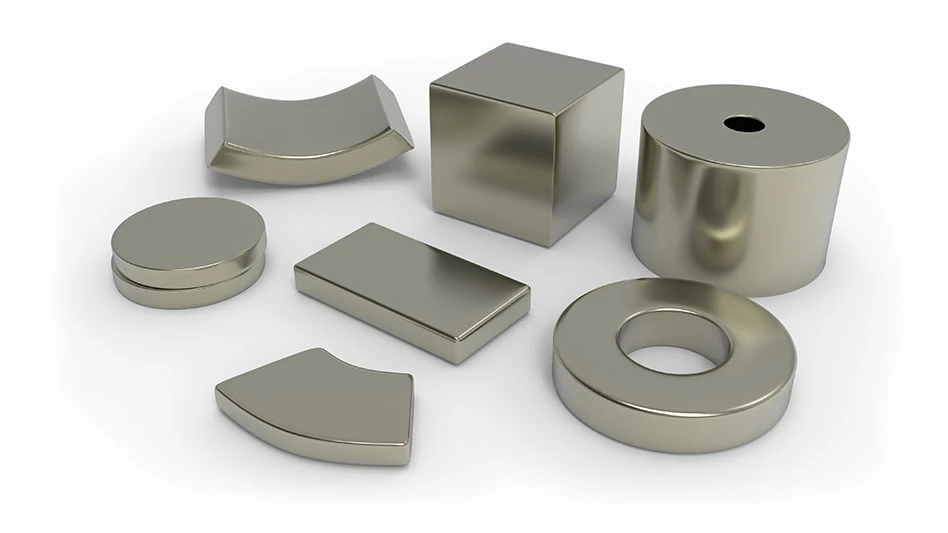

According to the report, REEs comprise 17 elements, four of which are most commonly used in REE magnets: neodymium, praseodymium, dysprosium and terbium. These four elements comprise roughly 30 percent of overall REE volume but represent more than 80 percent of their value. “Moving forward, global demand for magnetic REEs is expected to triple from 59 kilotons (kt) in 2022 to 176 kt in 2035, driven by strong growth in electric vehicle (EV) adoption, which is outpacing the substitution of REEs with copper coil magnets, as well as the high rate of renewable capacity expansions in wind.”

Given the absence of production forecasts for China, the announced project pipeline could fall short of demand requirements by 60 kt, or roughly 30 percent of total estimated demand in 2035, the report notes.

While REE demand is geographically distributed widely, China contributed more than 60 percent of the mined supply and more than 80 percent of refined supply in 2023, McKinsey notes. Additionally, recent geopolitical developments and their effects on trade have piqued interest in establishing local REE value chains across major geographies; however, the report says, current pipelines and trajectories likely will be insufficient over the next five to 10 years, necessitating recycling.

“Magnet production could consume an estimated 176 kt of REEs in 2035. Meanwhile, the REE value chain is expected to generate about 40 kt of preconsumer scrap, originating from magnet design and manufacturing steps, as well as 41 kt in postconsumer scrap from various end uses reaching end of life,” according to the report. However, most downstream magnet manufacturing occurs in China, meaning most REE preconsumer scrap will be recovered in that region. “By contrast, scrap from postconsumer sources will likely be geographically diverse, although true supply could remain limited to only a few kilotons because of recovery challenges related to already-collected magnets.”

More than 80 percent of REE postconsumer scrap originates from consumer electronics, appliances or internal combustion engine vehicle applications and takes the form of relatively small magnets for motors, actuators and sensors, for example, according to the report. “Although these applications will likely remain relevant over the next 10 years, scrap from BEV [battery electric vehicle] drivetrains, industrial motors and wind turbines could reach a similar magnitude, providing a new pool of larger magnets containing higher shares of valuable heavy REEs.”

Collection and recovery of REE magnets pose challenges, however, given low collection rates for devices that currently use REE magnets, the authors note. “Even if REE magnet collection is improved, materials will likely not be recovered across most applications, especially those with small or medium-sized magnets. Doing so would require dedicated separation of the magnet for further processing, which is a practice currently not adopted within existing recycling value chains focused on high-value or high-volume materials (such as gold and copper or aluminum and steel).”

According to the report, manually processing these devices to remove the magnets would be cost-prohibitive. Therefore, new approaches will be needed to recover these REEs, with McKinsey noting that some industry and research organizations are exploring targeted separation using automated robotic disassembly, bulk magnet isolation using hydrometallurgy and pyrometallurgy, hydrogen-based processing and extracting REEs from mine tailings. “Many of these technologies are still at R&D or pilot stages and need to be significantly scaled before they can be proven at the industrial level,” the authors note. “Tapping into the mostly unaddressed pool of postconsumer scrap will likely require players to think through how REE recycling can be integrated into current recycling ecosystems,” such as by adding new steps into established processes or rethinking process chains.

The report suggests that producers and manufactures help recyclers by providing transparency on magnet location, composition and value. “Powering the energy transition’s motor begins with understanding the dynamics around scrap pools, which technologies are competitive today and which will be competitive in the years to come and how to build alliances and integrated value chains to help those technologies get off the ground.”

Latest from Recycling Today

- SHFE trading expansion focuses on nickel

- Maverick Environmental Equipment opens Detroit area location

- International Paper completes sale of global cellulose fibers business

- Building a bridge to circularity

- Alton Steel to cease operations

- Nucor finishes 2025 with 14 percent earnings decline

- Algoma to supply Korean shipbuilder

- Improving fleet maintenance management across multiple locations