Each year when the Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries (ISRI) gathers for its annual convention, several thousand recyclers attend not only to talk about secondary commodities markets but also about the nuts and bolts of scrap processing.

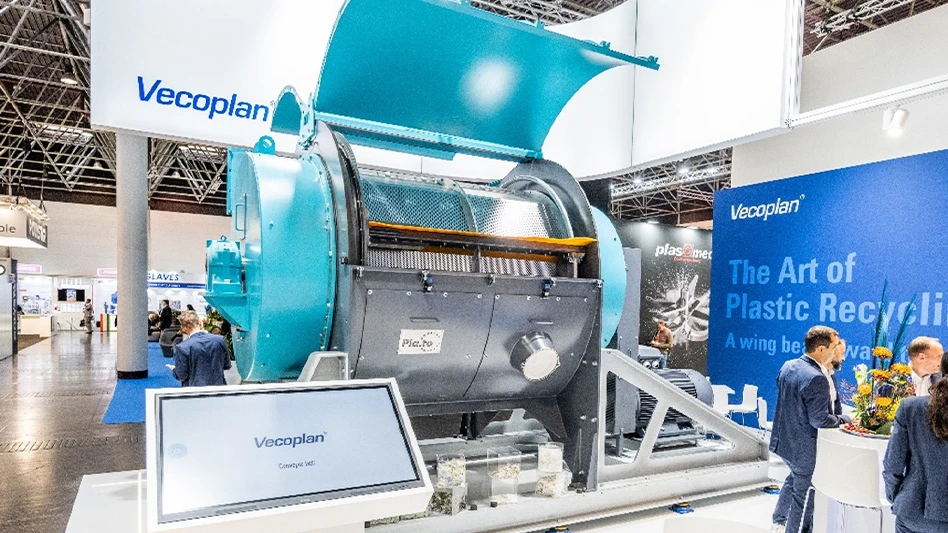

ISRI2018, like the annual conventions before it, featured an exhibit hall full of equipment and technology designed to help recyclers carry out the industrial portion of their work—including how to shred materials in ways to yield maximum profits.

The convention also included sessions on many topics, with several of those touching on how both the markets for shredded materials are changing and how technology is evolving to meet new challenges. The mid-April ISRI2018 convention, which took place in Las Vegas, was set amidst a first half of 2018 when news on many fronts is affecting the way recyclers shred automobiles, appliances, electronic equipment and any number of other obsolete materials.

Feedstock considerations

For several decades, ferrous scrap processors have been gravitating toward shredding as a preferred way to process their scrap. Scrap purchasers, electric arc furnace (EAF) steel mills in particular, have shown a preference for dense ferrous shred that can meet their chemistry specifications

While dense ferrous shred remains a highly traded commodity, the chemistry part of the equation can at times be problematic and it was the topic of discussion at one ISRI2018 session.

Making iron from raw materials may be one of the world’s longest-running manufacturing sectors, but the foundry industry in the last several decades has been infused with impressive amounts of change, according to Brett Fisher, a vice president with United States-based Neenah Foundry. He said the emergence of dozens of new iron alloys also has made ferrous scrap processing more complicated.

In the past six decade there has been an expansion in the types of gray and ductile iron produced by the foundry sector, with each new type of iron representing a different mixture of metallic alloys.

Ductile iron was not invented until 1949, and for many years after that, said Fisher, “There used to be two types of gray iron and three kinds of ductile iron.” Now, said Fisher, with iron users such as automakers seeking higher strength or lighter weight types of metal, there are 10 types of gray iron and about 50 types of ductile iron on the U.S. market and entering scrap yards.

“All have different chemical requirements—it has changed the landscape from the process standpoint,” declared Fisher, noting that melt shop managers at foundries will have different scrap specifications depending on the type of iron being produced in that batch. Scrap processors, meanwhile, can differentiate themselves by being familiar with and segregating some types of gray and ductile iron.

In general, said Fisher, Neenah Foundry prefers scrap with “good density” and with minimal amounts of “residual alloys,” and it values consistency in size, density and chemistry. Depending on the type of iron being produced, melt shops may often consider lead, antimony and boron as “deleterious” or unwelcome.

“Many of you who supply scrap can appreciate how this has become more complicated,” said David Borsuk of U.S.-based Sadoff Iron & Metal Co., who moderated the session at which Fisher spoke.

Jim Wiseman of U.S.-based SMART Recycling Management, who has 40 years of scrap industry experience, said the steel mill sector also has been narrowing and tightening its ferrous scrap chemistry requirements. In the U.S. region where he operates, said Wiseman, foundries are now “very specific on chemistries [and] steel mills are getting to be the same way.”

He continued, “As a processor, you may encounter mills that test incoming [scrap] chemistry very carefully. One mill asked for the metallic yield of the shred I sold.” This can be tricky for shredding plant operators, said Wiseman, because they are “not shredding the same identical products every day,” so the yield will change.

Stated Borsuk, “We’re part of [their] supply chain and our responsibility is ever-increasing. We as quality suppliers are going to have to sharpen up our game and have procedures in place” to measure chemistry and yield.

Borsuk said offering upgraded or improved chemistry may start with what is fed into a shredder. Plant operators may have to ask themselves, for instance, regarding increased copper content in their ferrous shred, “Is it from rebar being shredded? Is it from the wire in cars? Understanding what your [shredder] inputs are is going to become more and more critical.”

Some markets close, others open

Beyond complications in the U.S. ferrous shredded scrap market, the Chinese government’s growing list of restrictions on imported materials also is affecting the way recyclers around the world process and shred materials.

At the ISRI2018 Spotlight on Aluminum, Liu Wei, deputy secretary general of the China Nonferrous Metals Industry Association Recycling Metals Branch (CMRA), said the U.S. ranks first in terms of supplying aluminum scrap to China at a rate of 28.5 percent, followed by Hong Kong at 26.7 percent and Australia at 12.3 percent. (Much of Hong Kong’s material likely has traveled first from somewhere else.)

Much of this scrap comes in shredded form. Although the importing of most shredded metal has not yet been specifically banned by China’s government, it’s tight restrictions of 1.0 or 0.5 percent contamination (depending on the commodity) may yet have an impact on the volumes shredding plant operators can send to China.

China’s scrap imports (referred to by China’s government as “solid waste imports”) declined by 54 percent from February through March of 2018 relative to the same period in 2017. However, said Wei, aluminum scrap imports decreased by only 9 percent during that same period.

The Chinese central government plans to ban imports of Category 7 scrap (which includes baled wire and cable and scrap motors) by the end of 2018, he said, noting that as of 2017, this material accounted for 27.7 percent of aluminum scrap entering China. That was down from a rate of 41.9 percent in 2016.

Wei also said aluminum scrap generation within China has been growing at an annual rate of 10 percent, adding that the country expected to replace its aluminum scrap imports with domestically generated material by the end of 2019. If that forecast is accurate, shredding plant operators will be examining the settings on their downstream sorting systems to focus on serving either the domestic market or buyers in other nations.

In the ferrous sector, China has not dominated global trading in the past two decades in the same way it has for copper and aluminum scrap. However, China’s ability to supply itself with ferrous scrap also will have ripple effects on the global market.

Among ISRI2018 attendees was Diego Arróspide Benavides of Peru-based electric arc furnace (EAF) steelmaker Aceros Arequipa, who said he was there in part seeking stronger connections with North American scrap suppliers. According to Benavides, Aceros Arequipa is preparing to double its capacity in a nation that has a ferrous scrap supply deficit.

In 2017, China imported some 900,000 metric tons of ferrous scrap from the U.S. With China’s ferrous scrap deficit disappearing, most analysts agree, Benavides told Recycling Today Peru is part of a Latin American region overseas scrap recyclers should be examining.

Ferrous scrap broker Nathan Fruchter of U.S.-based Idoru Trading Corp., who spoke at ISRI2018’s Ferrous Spotlight session, referred to Bangladesh as “probably the most important newcomer’s market” in the sector. “Bangladesh is the new darling of the ferrous scrap export market,” he told Recycling Today. “With a population of over 160 million, it is one of the most densely populated countries. There’s not much room to build out, so they have to build up.” That, he observed, means a reliance on structural steel.

Also in Bangladesh’s favor, said Fruchter: “They are finally enjoying some political stability in the last four years, which has led to good economic growth and investments into the domestic steel industry in the previous two to three years.”

In 2016, said Fruchter, “The Bangladeshi government took a few measures to protect domestic steel production by imposing high duties on imported semis and rebars, hence boosting the local steel mills. Thus, the banks are now also more inclined to give larger loans to the steel producers. The majority of steel producers in Bangladesh are either induction based or EAF, requiring imported ferrous scrap. Bangladesh is expected to import more than 3 million tons of ferrous scrap in 2018. Is it any wonder that they are the new darlings of the ferrous scrap export market, if you consider that in 2015 they only imported about 500,000 tons?”

Fruchter is bullish the country will continue to need imported ferrous scrap, shredded or otherwise. “I expect strong economic growth to continue, but remember there are some constant reminders of setbacks, like the threat of heavy flooding due to out of control rains Bangladesh gets; and then there’s always a threat of a political shift. They hold national elections later in 2018. Let’s hope they stay the course,” he commented.

Latest from Recycling Today

- Equipment from the former Alton Steel to be auctioned

- Novelis resumes operations in Greensboro, Georgia

- Interchange 360 to operate alternative collection program under Washington’s RRA

- Waste Pro files brief supporting pause of FMCSA CDL eligibility rule

- Kuraray America receives APR design recognition for EVOH barrier resin

- Tire Industry Project publishes end-of-life tire management guide

- Des Moines project utilizes recycled wind turbine blades

- Charter Next Generation joins US Flexible Film Initiative