It's junk, yes, but it's worth too much to stand around for long.

That's the one thing people just don't seem to understand about the scrap heaped in PSC Metals' yard next to the interstate and the downtown riverfront, says a manager there.

"They see a pile and think the same one is still there, but we turn our shredder piles at least five times a month," said Greg Gillespie, the yard's general manager. "If you came here in a week, every bit of this will be gone. We don't hold on to too much."

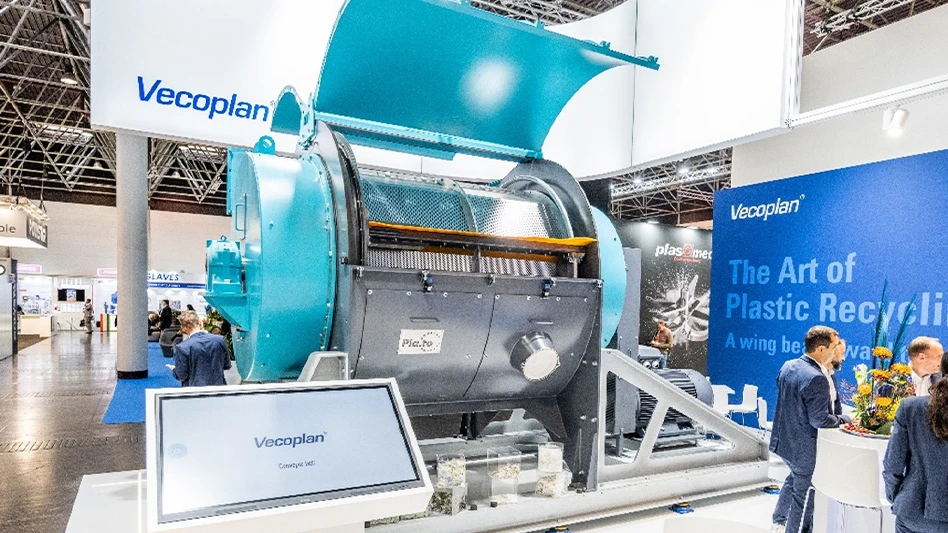

Behind Gillespie, a crane took a battered pickup truck from a three-story pile and loaded it onto a conveyer belt. The truck dropped into PSC's month-old, state-of-the-art shredder.

A rotor with 10 steel hammers, each 335 pounds, beat the truck into hundreds of arm-sized pieces. A blower separated upholstery, plastic and other worthless trash. A vacuum trapped noxious gases. Computers kept the whole operation from jamming up, while a single technician watched from a booth.

This may be a dirty business - turning Nashville's old cars, appliances and castoffs back into their raw selves - but it's also a surprisingly sophisticated and lucrative one. The Second Street yard's success, say city officials and civic boosters, is perhaps the best explanation why PSC and its hard-to-appreciate mounds of metal have hung on, even as gentrification has spread from downtown to east Nashville.

The scrap market is booming, the effect of surging demand for metals and raw materials in far-away places such as China and India. And the benefits trickle down all the way to Nashville.

This year, PSC's Nashville yard, by far the larger of its two locations in Middle Tennessee, will generate about $100 million in revenues. The yard employs 125 people and is active about 20 hours a day, including many weekends. Its annual property tax bill adds $300,000 a year to city coffers, according to Metro records.

But time could be running out for PSC Metals, with its five-decade history of metal crunching on the east bank of the Cumberland River.

Private developers have expressed an interest in the more than 50 acres that PSC owns or controls through long-term leases.

Meanwhile, a Metro consultant is working on a plan that would take much of the company's land for a riverfront park.

The cost of buying the land beneath PSC and its neighbors - as much as $100 million, by most estimates - makes this one of the trickiest urban redevelopment projects Nashville will face. So many details need to be worked out that Gillespie puts them out of his mind as his workers pound away.

"I don't feel threatened," he said. "Something will probably happen someday. Is it going to be next month, 10 years or 10 days from now? I have no clue."

'Highest and best use'

The question of redeveloping the land under PSC and its industrial neighbors has come up several times in the past decade. Ideas have included using it as a site for a convention center, a baseball stadium and an amusement park.

"Everyone has become very aware this is not the highest and best use for that land," said Kate Monaghan, executive director of the Nashville Civic Design Center, a local nonprofit that is holding forums on riverfront development, including one next week.

Perhaps the most ambitious proposal emerged last month. Hargreaves Associates, a consultant hired by Metro to come up with plans to revitalize the waterfront, proposed turning the entire area into a mixed-use neighborhood with a riverfront park and marina. One idea would set the area off as a man-made island.

"It comes down to the public will," Monaghan said. "It's just a math problem at some point."

But executing that plan would mean uprooting a yard that has processed metals in its current location since 1954, when the Steiner family merged their scrap business with a company owned by the Liffs and bought a site that had been a city dump.

The yard continued operations through a change in ownership in 1997, when it was bought by a Hamilton, Ontario-based Philip Services Co. It also stayed open through a securities fraud investigation and two bankruptcies, one of which led to Philip's purchase by billionaire financier Carl Icahn.

The scrap yard succeeds because it serves as a key recycling post for the 100-mile radius centered on Nashville. Much of the yard's raw materials are brought in by individuals: pickup trucks laden with farm equipment, cars loaded with appliances, peddlers carrying cans.

From this, the scrap yard turns out about 25,000 tons of steel and about 1,000 tons of other metals a month. Three-quarters of the steel leaves the yard by barge. Everything else is shipped out by truck or train.

Rising commodity prices have made this a profitable time for PSC, Gillespie said. At $1 a pound, a single, 30-ton pile of aluminum can sell for $60,000.

Workers' main jobs are separating the metals into piles and preparing them to ship. They use everything from mundane tools, such as cranes and blowtorches, to a sophisticated machine that uses magnetic fields to push a slip of aluminum out of a pile of debris.

This equipment can be expensive. A gamma-tech analyzer, which can measure the purity level of a batch of steel, cost more than $1 million to purchase and install last November, Gillespie said. Buying and setting up the new shredder last month cost $750,000.

Complex move

The equipment is difficult - but not impossible - to move. Putting in the shredder meant shutting down for 10 days, during which PSC accumulated a mountain of inventory that it is still trying to work down.

A similar disruption occurred five years ago when PSC relocated its barge loading facility, its truck scales and railroad scales to make way for the Korean War Veterans Memorial Bridge, the span that now links Gateway Boulevard with Shelby Avenue in east Nashville. That project hints at how complex moving the entire facility would be.

The Tennessee Department of Transportation invoked the power of eminent domain, but it still had to pay $5.3 million for four acres of land, a small corner of PSC's operations. Extrapolating from that, city officials estimate it would take about $100 million to acquire the more than 90 acres of land under PSC and its neighbors. The estimate does not include the cost of cleaning up the land.

That money would probably have to come from the private sector. Mayor Bill Purcell said his administration would not spend tax dollars to buy land that should entice developers on its own. He also said it would be unwise for the city to take on the environmental liability.

The city's role would probably involve finding a new site for the scrap yard, Purcell said. Officials prefer to keep it in Davidson County because of its tax revenue and its important part in handling the city's trash.

But finding a new site could also be difficult. PSC Metals needs ready access to the river, rail lines and highways to send and receive scrap. It needs a central location that small operators can reach easily.

And it would need to set up its new operation before it shut down the old one; otherwise the city could run awash in unprocessed metals, observers and company representatives said.

The tortured recent history of PSC Metals' parent company is another hurdle. Instead of an independent local business, the Nashville scrap yard is now just one operation in Icahn's New York-based empire of investments in dozens of companies scattered around the world.

"It's not as if there's a CEO on it that we can talk turkey with," said Mike Jameson, the Metro councilor who represents the area.

Improving neighborhood

Across the river from PSC's new barge terminal, Rolling Mill Hill stands on a high bluff overlooking the Cumberland. Work on an upscale residential and commercial development has just begun there, in the derelict campus of the city's old municipal hospital.

Projects such as these raise the likelihood that PSC Metals and its neighbors will be moved within a few years, observers said. A little over a decade ago, the scrap yard was just one eyesore in a sea of industrial blights that lined both sides of the river.

Now, LP Field stands where a steel mill once did. A baseball stadium is planned for the site of the city's demolished incinerator. Industrial buildings and parking lots south of Broadway are being cleared to make way for office towers, condos and a symphony hall - many of which will have a direct view of the scrap metal yard across the river

Those changes have sparked even more ambitious ideas for PSC's land. Most of the ideas have fizzled, but it's the fact that they keep coming that encourages city leaders.

"Some of them will be hare-brained, but the critical thing is that people keep expending energy on it," Purcell said.

But ideas aren't what get land moved, says Gillespie. Money is. And until someone comes up with a way to finance one of the ambitious plans for its land, PSC simply will keep grinding its scrap into cash.

"I've been here about 11 years, and I've seen half a dozen of these ideas comes through, some good, some bad," Gillespie said. "The question I have is, who's going to pay for it?" Tenessean

Latest from Recycling Today

- Ocean freight interruptions poised to continue

- Danieli to supply shredder to Australian company

- Equipment from the former Alton Steel to be auctioned

- Novelis resumes operations in Greensboro, Georgia

- Interchange 360 to operate alternative collection program under Washington’s RRA

- Waste Pro files brief supporting pause of FMCSA CDL eligibility rule

- Kuraray America receives APR design recognition for EVOH barrier resin

- Tire Industry Project publishes end-of-life tire management guide