New plastic sorting equipment has to deal with challenges like PET-G (polyethylene terephthalate glycol) and bio-plastics. Improved cutting geometries are designed to make size reduction more effective and to give the end-product nice, crisp edges. With the energy-efficiency claims of products coming to market, plastics recyclers have a reason to look at long-term ROI as well as immediate capital costs.

“This isn’t just about making big pieces small,” says David Lefrancois, president of Herbold Meckesheim USA, Smithfield, R.I. “You need to know the volume of your material, its composition and what kinds of label stock you are dealing with,” he adds.

“Nobody has one shredder that is ideal for everything,” says Charles Hildebrand, regional sales manager for UNTHA America, Newburyport, Mass. “You can optimize a machine for one application but not all materials.”

Recyclers must determine what their incoming material stream is, and they may need a crystal ball to see what is coming in the future. PET-G is one such up-and-coming plastic. A glossy material used for labels and sleeves, it cannot be sorted as regular PET, according to Alain Descoins, Pellenc vice president of sales and engineering for the U.S. market.

“More bio-plastics such as PLA (polylactic acid) are entering the market,” he continues. Most cannot be recycled with the petroleum-based resins. “This could generate a need to sort them at the MRF (material recovery facility) level,” says Descoins.

OPTICAL AIDS

He suggests MRF operators consider employing optical sorting for separation in addition to the more traditional mechanical screens and air classifiers. “At the MRF level, optical sorters could be used at various points on both the fibers and containers lines,” he notes. Descoins points out that flexible films missed by upfront mechanical screens normally require several full-time equivalent hand sorters. “[Flexible films’] presence poses various challenges to MRFs: They reduce the efficiency of ferrous magnets by allowing steel cans wrapped in plastic film to pass by the ferrous magnet [and] they clog disk screens. Films along with rigid plastics can be removed automatically from the fiber stream with optical sorters,” he says.

Once the plastics are separated from other recyclable materials, a MRF can use a two-stage optical sorting system to separate various grades of marketable plastics. The first stage sorts by resin, the second by color. Descoins says he sees a breakdown of proposed grades including mixed rigid plastic containers, pigmented PET, clear PET, colored HDPE (high-density polyethylene) and natural HDPE.

At the reclaimer’s level, optical machinery sorts individual resin types for further processing. Most baled plastics from MRFs require additional sorting, especially the ones coming from MRFs with manual sorting or single-stage automated sorting, according to sources. Reclaimers scrutinize bales for contaminants, such as PVC or metals, but also for variations of resins such as PET–G.

“Glycol-added PET is praised by packagers for its glossy appearance and is used more frequently as sleeving on PET bottles,” Descoins says. However, it cannot be recycled as-is in a PET reclaiming facility. He says new optical sorting equipment can allow recyclers to positively identify PET-G from PET.

Descoins notes that California is leading the pack in identifying and sorting bio-plastics, which are made from corn or other plants. He received a grant to work with 12 MRFs in California to see how they can handle bio-plastics and how much material actually is out there.

Descoins says optical sorting solutions can be powerful tools for plastics recyclers as well. “First, as they are not using mechanical separation, these machines can deal with a high tonnage,” he says. For instance, you can sort about 8,200 pounds per hour of containers with a 47-inch wide Pellenc Selective Technologies machine, sorting out 60,000 PET items per hour with an efficiency and accuracy rate of 95 percent, Descoins says. “This would require about 24 manual workers to do the job,” he says.

He says an optical sorting machine requires 25 feet of linear space, though units can be stacked to save space.

“Equipment has really gotten bigger and faster,” says John Farney, national sales manager for Cumberland Engineering, New Berlin, Wis. “Markets are coming back, so recyclers want to process more material, faster.”

| POWER DOWN |

|

High-efficiency motors are a long-term investment. While 80- to 85-percent-efficiency motors were a big deal a decade ago, today’s recyclers should demand 95-percent-efficient motors, says John Farney, national sales manager for Cumberland Engineering, New Berlin, Wis. He notes that most power companies have grant programs that will make up the difference in cost between a low-efficiency motor and a high-efficiency motor, such as a Toshiba Gold. Farney also encourages recycling operations to look at capacitive load balancing to stabilize their operational loads. This is not just something that is being done by recyclers in California to be eco-friendly, he notes. Recyclers in the Midwest and South are aware of every dime spent and are doing whatever they can to contain energy costs. “Utilities penalize you for spikes when you start a system,” Farney notes. He recommends users “soft start” their systems and by avoiding starting four or five devices at the same time. “Bring on the low-amp devices first, then the big ones,” Farney advises. In addition, better cutting geometries can use less energy and are may not cause as much friction-related breakdown of material. |

PROCESSING PLASTICS

While most recyclers focus on output production, Lefrancois says it is important to know the contaminant level going in. “If you want output of 2,000 pounds per hour, your input can’t be 2,000 pounds…you probably are dealing with contaminant levels up to 40 percent, and you have to allow for that,” he says.

It also is important to know what kinds of label stock will be coming through, according to sources. Paper handles differently than plastics and water-soluble glues process differently than other glues. Each aspect can change the output.

Slow and steady can win the efficiency race. “Don’t go feast or famine. Don’t strain the equipment,” Farney says. That can mean adjusting volumes so machines operate at a steady rate all day long.

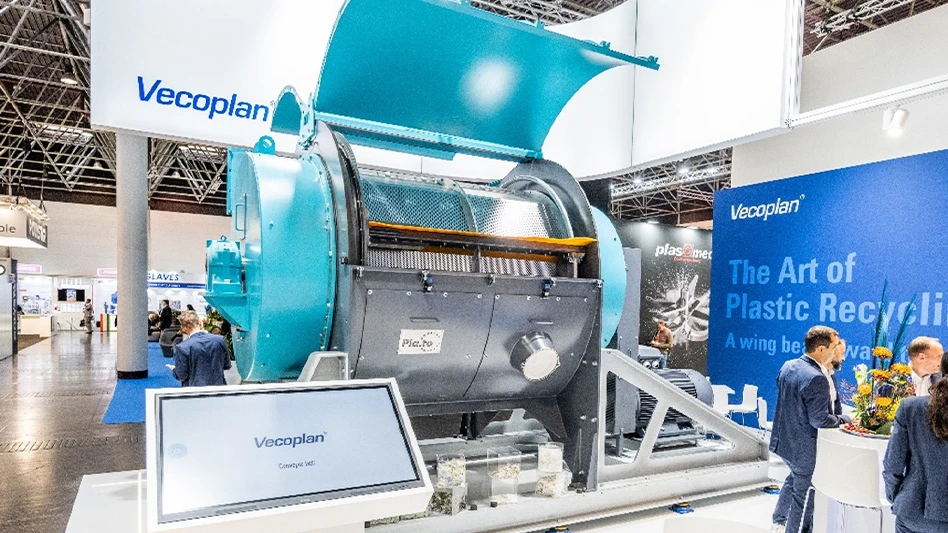

For Herbold Meckesheim, wet granulation offers efficiency. “We prefer to wash as part of the process,” Lefrancois says. He likes to compare the process to a home washing machine, where the agitation provided by the equipment and friction created by the material shakes the dirt loose and provides a clean product. The company’s system handles PET, PET-G, HDPE (high-density polyethylene) and films, whether rigid or soft.

Hildebrand recommends a four-shaft shredder for films and other materials with low melting or softening points.

“The four-shaft runs at a lower speed and will not melt the material,” he says. “PLA definitely calls for a four-shaft machine.” PLA softens at 105 degrees. On a hot day, a clamshell box can change form inside a truck, sources say.

On top of that, Hildebrand says the slower speed of the shredder means the material is less likely to wrap around the shaft than it is with a single-shaft machine. “For materials with higher melting points, like HDPE and polypropylene (PP), you can use a single shaft,” he adds.

Hildebrand notes that the format of the material makes a difference, too.

No matter what system is being used, Farney says recyclers should take the material out of the grinder as soon as it is ready. “Don’t over-grind,” Farney says, adding that no machine will be dust free. But, it is possible to minimize dust with good cutting geometries and better removal of material from the system.

IS USED WORTH IT?

While he deals both in new and used equipment, Farney says used equipment may not be worthwhile.

“Used equipment rarely is a bargain. Too many people want to spend $50,000 and make a million,” Farney says. “Start from scratch,” he advises.

He notes that one of his own 1972 Cumberland granulators was a good product in its day. “But you can’t expect the performance and efficiency from that vs. a new machine.”

Not only can a recycler get soaked on power costs, it may be difficult to get replacement parts for older machines in a timely manner. “Can we get replacement parts?” Farney asks. “Yes, we can. But you won’t be getting them overnight.”

New equipment may be more efficient overall. “It is important for the recycler to know market specifications—typically requiring less than 2 percent by weight of contamination—in order to define final sorting goals,” Descoins says.

Numerous factors contribute to achieving optimum automatic sorting efficiency, including how well the materials are spread out on the conveyor, upfront contaminant removal equipment and sorters, air classification and eddy current systems to remove paper, labels, aluminum, etc.

Researching the market, including establishing a projected value for sorted materials on local markets and in Asia, also is a critical step.

“Commercial recyclers, on the [one]hand, are convinced of the need for optical sorting, as its efficiency cannot be matched by any other technologies in most cases. Human eyes can easily detect colors but are blind when it comes to resin type,” Descoins says. Meanwhile, plastic film recyclers crave automatic solutions to efficiently sort various film types.

“Know the full spectrum of materials and form-factors you will be handling,” Hildebrand says regarding size reduction. This can range from Little Tykes plastic toys to milk bottles or film. “That will dictate the cutting process and screens,” he says. “Knowing this will give the manufacturer a better feel for what the machine will have to do.” Lefrancois notes that commercial operators are becoming savvier as they realize the value of doing their homework before buying or upgrading. “It used to be people just took their plastic and baled it,” he says. “Now you see a lot more segregation. Recyclers are buying presorted bales. It is not helter-skelter anymore.”

It is unlikely that those bales are 100 percent clean. Lefrancois figures the norm is closer to 70 percent. “Everyone wants it better—but today it is a lot better than it was in the past,” he says. “It will keep improving.”

The author is a freelance writer based in Cleveland. He can be contacted at curt@curtharler.com.

Latest from Recycling Today

- Equipment from the former Alton Steel to be auctioned

- Novelis resumes operations in Greensboro, Georgia

- Interchange 360 to operate alternative collection program under Washington’s RRA

- Waste Pro files brief supporting pause of FMCSA CDL eligibility rule

- Kuraray America receives APR design recognition for EVOH barrier resin

- Tire Industry Project publishes end-of-life tire management guide

- Des Moines project utilizes recycled wind turbine blades

- Charter Next Generation joins US Flexible Film Initiative