As 2018 came to an end in the United States aluminum scrap market, plenty of mill and secondary grade scrap units were available to go around, while demand for these units was weak and spreads continued to be very wide. Mills continued to be adequately stocked, with no need to purchase additional scrap units, and demand for secondary scrap was light as secondary smelters worked down existing inventories before the end of the year.

Changes to China’s scrap import policies in the second half of this year will likely further affect the U.S. aluminum scrap market.

Persistent conditions

In early 2019, the market has picked up where 2018 left off—slow demand because mills and secondary producers have adequate scrap on hand, an ample supply of scrap at the yards and very wide spreads. For example, the spread between P1020 and mill grade segregated scrap prices in January 2019 was around 23 cents per pound, the same as it was in late 2018, and two-cents-per-pound wider than January 2018.

As of mid-January, scrap supply was not an issue in the market, as winter weather had yet to impact peddler traffic to the yards; shredders were still generating zorba and twitch; and industrial scrap continued to be generated at strong levels. However, the severe winter storms and extreme cold temperatures experienced in late-January in the Midwest likely will affect load deliveries and peddler inflow and will cause a slowdown in shredding activity. While this will curb scrap generation for a short time, it will not cause the scrap surplus to shrink significantly as such dynamics would need to be more than a short-term event to change the current oversupply situation.

As the early weeks of 2019 progress, mills and secondary producers are expected to come back to replenish scrap supplies that were worked down at the end of the year. On the mill grade side, demand isn’t likely to resume right away in 2019. With high scrap inventory at mills, they have no pressure to buy with wide spreads and ample availability. In fact, CRU understands that new deliveries are not being booked until the second quarter and that some orders from November/December 2018 have not been scheduled for delivery yet. This will likely support continued wide spreads.

In addition, with a surplus of obsolete scrap units available in the market at wide spreads, secondary smelters are not moving up the food chain to obtain higher grades of scrap, removing what would be a source of additional demand for mill-grade units. However, for secondary grades, demand has started to come back slowly at the start of the year as secondary smelters look to replenish inventories at low prices, and automotive manufacturers, die casters and original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) come back after end-of-year slowdowns.

Like most of 2018, as of the start of 2019, there is just very little demand outside of contractual shipments, and with scrap continuing to be generated, it remains plentiful in supply. We understand that some mills have booked less scrap volumes on contract for 2019, as they look to take advantage of lower spot prices. This has surprised some scrap dealers, who had anticipated mills to fully contract and take advantage of historically wide scrap spreads.

A potential scenario exists that when current inventories are depleted and mills enter the market for scrap units later in the year, a shift could occur from a buyers’ market to a sellers’ market.

Dramatic changes

A drastic change to U.S. scrap market dynamics has come in the form of an announcement from the Chinese government that as of July 1, 2019, scrap items under HS code 7602000090 are being moved from the list of raw materials that can be imported into the country without restrictions to the list of solid waste items for which imports are restricted. To give a sense of the impact, in 2018, China imported more than 2 million tons of aluminum scrap from all trade partners under the HS code 7602, 99 percent of which would now fall under the restricted list.

The particular customs code in question (HS code 7602000090) includes “Category 6” scrap items. Category 6 aluminum scrap includes twitch/zorba material, which makes up a vast majority of aluminum scrap that the U.S. exports to China. According to current regulation for restricted imports, the importers will need to apply for a license to bring in these products.

The impact on the U.S. scrap market will be huge. Imports of aluminum scrap from the U.S. to China already are subject to a 50 percent import duty, which has greatly reduced volumes going to China from the U.S. According to the latest trade data, exports from the U.S. to China were down by nearly 40 percent through October 2018.

With the move of Category 6 scrap to the restricted list, on top of the existing 50 percent import duty, the writing seems to be on the wall. Unless policy changes are implemented between now and July 1, U.S. exports of such aluminum scrap grades to China will effectively end.

In addition, the 50 percent import duty on U.S. aluminum scrap into China likely will hinder any potential efforts by importers/exporters to ship large volumes to China during the first half of the year in advance of this deadline. If exports to China effectively end at the beginning of the second half of 2019, the current U.S. scrap glut would become larger, unless alternative destinations are identified.

In response to lower demand from China and the 50 percent import duty, U.S. exporters were successful in finding alternate homes for their units in 2018. As a result, total U.S. exports of aluminum scrap actually rose in 2018, as gains in exports to other countries, such as India and Malaysia, outweighed the large decline in exports to China. However, CRU questions the ability of these markets to sustain such levels of imports. Even if these alternate homes could sustain 2018 levels, it is highly unlikely that they could absorb the full weight of volume loss that would occur if U.S. exports to China ceased in the second half of 2019. As well, this would not be able to replace the amount of aluminum scrap that goes to China on an annual basis.

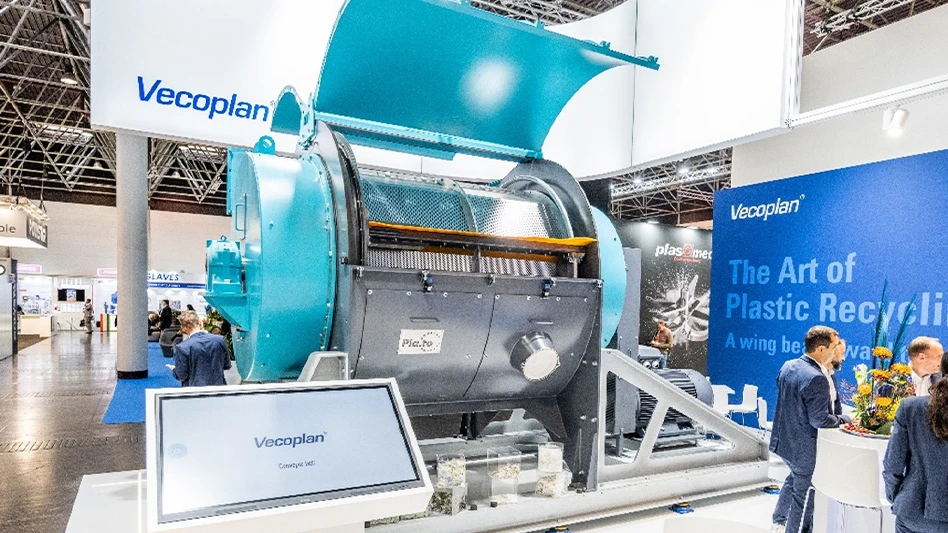

Without permanent long-term new homes to go to, this material that once went to China will stay in the domestic U.S. market. As the zorba that typically goes to China is not a product that is used in the U.S., it needs to undergo further processing to turn it into a twitch package that can be sold here. This could lead to an increase in capital spending to expand or enhance separation equipment at scrap processors.

The steel connection

Zorba generation is traditionally tied to shredding operations, which are driven by steel prices. U.S. steel prices had a good run in 2018, which incentivized shredding, thereby generating more zorba. This resulted in a glut of material in the U.S. market last year.

With scrap export volumes set to drop this year, this situation could become worse because even if more zorba is processed into twitch, the homes for twitch are limited. More zorba and twitch could pile up if shredding continues at the 2018 pace.

However, steel scrap prices have been weaker in 2019, which likely will have a negative impact on the amount of shredding that occurs. If so, this may be the lone factor that can pull in the reins on growing zorba and twitch supplies.

Mike Southwood is senior analyst, aluminum, for London-based CRU. He is based out of the company’s Pittsburgh-area office and can be contacted at mike.southwood@crugroup.com. More information on CRU is available at www.crugroup.com.

Latest from Recycling Today

- Equipment from the former Alton Steel to be auctioned

- Novelis resumes operations in Greensboro, Georgia

- Interchange 360 to operate alternative collection program under Washington’s RRA

- Waste Pro files brief supporting pause of FMCSA CDL eligibility rule

- Kuraray America receives APR design recognition for EVOH barrier resin

- Tire Industry Project publishes end-of-life tire management guide

- Des Moines project utilizes recycled wind turbine blades

- Charter Next Generation joins US Flexible Film Initiative